A focus point of devotion in the Lady of Ta'Pinu Shrine: the altar, and the Shrine's famous Marian image. Visiting shrines like this are the one and only kind of tourism I enjoy on holiday...

I am not good at tourism. Correction: I actively abhor tourism. I’m just not a fan of sweatily traipsing around over-crowded places, craning my neck to see “erudite stuff” obscured from view by crowds of eye-rollingly bored schoolchildren, getting lost in labyrinthine public institutions most likely haunted by a neo-Minotaur docent, and shoving over-priced stale sandwiches down my throat like a starved gannet for “lunch” on the go. Maybe I just do tourism wrong: this is probably true. Also, the bulk of my working life is spent reading, learning, thinking as precisely as possible about complex theories and problematics. Going to exhibitions and art showings and interesting film screenings is part of my research life, part of excavating cultural artefacts all around me to find their resonances with my specific research frameworks. So, on holiday, all I want to do is to channel my energies into actively not thinking: I want to kick back and go to the beach - I am very good at beaching - with a stack of really very silly books. My top recommendation for the latter is what are known in my house as the “sexy horsey books”, a series of well-written romance books by Bev Pettersen. No, “sexy horsey” does not point to any elegantly phrased tales of, shall we say, somewhat euphemistically, “paraphilic desire”. Pettersen immerses the reader into the world of serious horse training and jockey life, with well-drawn and thoughtful protagonists who have superb chemistry, propelling the romance plot along in fine style. Very much recommend, even if you aren’t very keen on horses. Horses as a species seem to have had a council meeting and decided unilaterally that they do not want me to be a rider…

Anyway. Today’s post is not actually about tourism/holidays/horses, or not entirely. The only type of tourism that I enjoy is visiting religious institutions and saints’ shrines in lands afar, witnessing modern devotional practice and culture that so clearly relates to the medieval saints I have spent years working on and have come to love. In September 2011, I went on holiday to the Maltese island of Gozo, a sun-drenched rock which does a fine line in fish dinners, sandy beaches and Catholic basilicas. St. George’s Basilica in Victoria is a beautiful parish church, originally dating to at least the fifteenth century. It’s the kind of place that is so resplendent you sort of worry if you should be let in or not, yet it is still a hub of regular popular worship, as testified by their YouTube channel filled with videos of services. The juxtaposition of features I superficially ascribe in my imagination to medieval worship spaces evoked in hagiographic narratives – including intensely rich decorations and a tangible aura of sacrality– with modern worshippers going about their business, as they do on any given day of the week, really astounded me. This is the medieval/modern religiosity connection writ large. It also serves as an effective reminder that medieval churches were communal, public spaces – there to be filled with the flock, spaces of dynamic interchanges – just as in St. George’s today. This is something I tend to forget, or let fall by the wayside, as I consider the descriptions of churches and religious services in narratives I study, as it is so different to my own reality.

"Dome of St George's Basilica" by Michael Caroe Andersen. Via Flickr. No, I can't believe I didn't take my own pictures of the Basilica either.

"St George's Basilica" by Michael Caroe Andersen. Via Flickr

Though St. George’s was utterly lovely, I was most excited about visiting another basilica on the island, the National Shrine of the Blessed Virgin of Ta’Pinu in Għarb, given my immense interest in pre-modern female devotion. My holiday-mates were very gracious, and let me do my “medieval-religious-detective” thing for a few glorious hours. The gallery below features some of the many, many, (perhaps too many) photographs I took during my visit. The exact origins of the Shrine are unknown, but it is first described in writing in the sixteenth century. (For a potted history of the site, see the relevant page on the Shrine’s website. See also Mrg. Nicholas J Cauchi's slim volume, Ta'Pinu Shrine: The Pilgrims' Haven, published by the Shrine in 2008.) Though the Shrine had a long history as a site of Marian devotion, events in the summer of 1883 ultimately increased its fame as a particularly holy site. Two villagers, Karmni Grima and Franġisk Portelli, frequently heard the voice of the Virgin Mary calling them into the chapel to pray in separate mystical incidents. Further, Portelli's mother was afflicted by a deleterious illness at the time, but achieved a miraculous cure after her sons (Franġisk and Nikol) paid special reverence to Our Lady of Ta'Pinu, and kept a lamp lit in front of her altar at all times. These events established the Ta'Pinu Mary as a potent miracle-worker and very effective intercessor with the divine. Throughout this post, I'll use "Ta'Pinu" to refer to the specific construction of the Virgin Mary worshipped at the Shrine.

Offerings for Ta'Pinu cover every inch of space in a side-room off the chapel

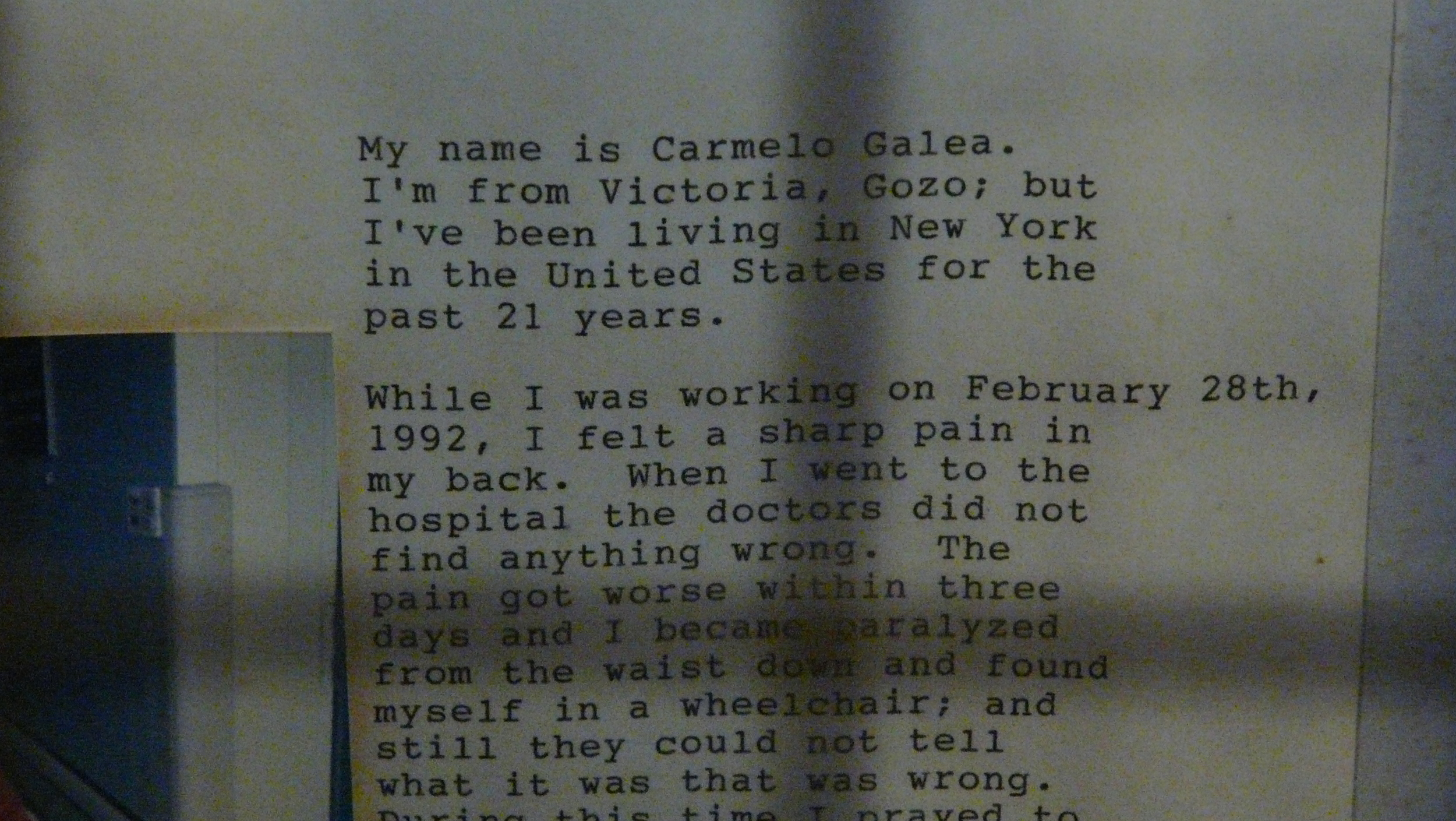

The basilica (including a chapel, newer sanctuary, and museum) is, as you might imagine, fantastically opulent, crammed with beautiful stained glass, images, niches, candles and on and on. What grabbed me the most, though, were the countless modern artefacts and letters given up to Ta’Pinu as votive tokens (ex-votos), either in the hopes of receiving healing miracles or as a form of payment for the reception of Ta’Pinu’s grace. These objects cover the walls in a kind of hopeful collage of piety in rooms adjacent to the chapel itself. Walking through these spaces feels a bit like going to a bric-a-brac table sale, but with each offering – however innocuous or banal – imbued with profound personal and spiritual meaning. Plaster casts, browned Polaroids, orthopaedic screws, baby blankets, scrawled notes, chopped-off hair braids, bent bicycle wheels, typed letters, dented crash helmets, rosaries, crisp white Christening gowns. Perhaps the meaning or such mementos is not just personal and spiritual, but rather personal-spiritual. These are tangible objects which relate directly to a given believer’s highly specific experiences: subject-specific vessels of faith. The orthopaedic screws, for example, are spiritual for one believer as they come from their own body, a difficult surgery with a successful outcome thanks to prayers delivered to Ta’Pinu. Such screws would mean nothing to the believer petitioning Ta’Pinu for the successful delivery of a baby. Instead, she offers up a Christening gown, a tangible manifestation that the holy virgin came through for her and allowed her baby to thrive. A sample of photographs capturing the mementos are below - for more, and for the gallery showing my trip to Ta'Pinu, scroll down to the bottom of the page.

Browsing through the halls of such personal-spiritual tokens, you’re struck by the evidence of Ta’Pinu’s efficacy in responding with grace to her devotees’ calls. This is substantiated further as visitors to the basilica are invited to offer up a specific prayer to Ta’Pinu, which is printed in various languages in framed prints near the altar. Visitors are also invited to petition Ta’Pinu by writing their prayers in a sort of “prayer pro-forma”, to be sealed in the supplied envelope, and deposited in baskets by the altar. You can also submit petitions to the holy woman online, via a web form. The Shrine also offers webcams for attendance at Mass and visiting the chapel from the comfort of your own home, though I couldn’t make either stream play when I last tried. Nevertheless, I’m delighted by the Shrine’s conscious interfacing with the digital world. It represents, to me, a means of expanding the intercessory capacity of Ta’Pinu ever onwards, and suggests an (anticipated) popularity for her cult. Moreover, leaning into the digital world suggests a response to the evolving lifestyles and associated needs of believers. Rather than excluding those who might wish to visit or call upon Ta’Pinu, the Shrine has developed its offering of rites and rituals to speak to the needs of a geographically dislocated – or simply busy – flock.

In 1998 a church dedicated to Ta’Pinu was opened in Bacchus Marsh, a site about 50km outside Melbourne, Australia, with the chapel being a replica of the original chapel in Gozo. For a brief history of devotion to Ta’Pinu in Australia, see here. See also Paul Harris’ short documentary film about the Australian site, below. As with the Gozitan Ta’Pinu Shrine, the Australian Shrine allows individuals to engage with the holy virgin online: by submitting prayers, requesting masses, and requesting candles be lit. It’s hard to avoid noticing, though, that the Australian site suggests monetary donations when you submit your prayer or mass requests and a flat-fee of $7 for lighting a candle. The prominence of such financial requests reflects, perhaps, the Australian church’s status as a relatively newly founded institution, in need of all the support it can get to equip its building and develop its ministry. In any case, the institution of the Australian Shrine, and its digital offerings, speak once more to an attempt to respond actively to the emerging needs of believers. It is an “All Nations Marian Centre”, and used by a variety of community groups from different ethnic backgrounds as a hub for Marian devotion, of which reverence of Ta’Pinu is just one form. In her Australian incarnation, then, Ta’Pinu represents the multiplicity of ways a believer can access the Virgin Mary, and relate to Her in ways that a believer feels fits their personal outlook and cultural heritage.

Why do I love visiting places of worship like Ta’Pinu? Why have I shared the pictures here? I think the photographed artefacts are, above all, interesting, and resonate with a kind of beauty inspired by the fervent hopes and faith that believers have poured into these tangible vessels of the banal horrors of everyday life. Additionally, I offer the pictures as a window into modern Catholic worship culture. By gazing through this window, I believe medievalists can better do the work of investigating medieval religion. I’m a scholar of medieval religious culture, but I work in a predominantly – almost entirely – secular environment. Exposing myself to modern Catholic praxes can be eye-opening. Rites and rituals that sometimes feel overwhelmingly distanced, that could somehow only take place in medieval hagiographies or religious narratives, can and do exist in various forms in modern Catholic worship, re-modulated to greater and lesser degrees to fit contemporary worship preferences, doctrines, and styles. And so, as I wend my way around modern spaces of devotion, my eyes grow ever wider and my mind becomes ever more blown.

The medieval saints and worship praxes I study are relics of the most potent kind: productive and animated artefacts which continue to exert power in the world, though they may be – technically, superficially – dead and gone. I’m not saying that there is a singular form of worship which exists, unchanged, from the medieval to the modern period. Rather, that there are demonstrable similarities between medieval and modern worship forms. Instead of bracketing of the modern from the medieval, I think looking at the modern iterations of worship can allow us to better understand and contextualise pre-modern religion, and the pre-modern era more generally. How did medieval believers react in this or that way to a given social/political/geographical/ideological event horizon? Moreover, I believe that we can better unpack the ways in which medieval believers responded to the Church – by reshaping their practices, exerting their own choices for where to put their faith in holy individuals – if we look at the ways in which modern believers do the same.

"Dia de los Muertes" - Jesse Means. Via Flickr. A large Santa Muerte atop the public altar on the Day of the Dead in Seattle, 2010

Undoubtedly, specific circumstances mould religious praxes, be they social, political, geographical or so on. Catholicism, medieval and modern, is not monolithic. Frankly, I wish I could speak Maltese so I could dig into sources on Ta'Pinu which reveal the significance of this representation of the Virgin Mary to the people of Gozo, and Malta more generally. Another example will have to suffice for now: the rise of devotion to Santa Muerte (“Saint Death” in Spanish) in Mexico, parts of the USA, Central America and further afield. Over the past few years, a stream of articles have been published shedding light on this “new” saint: see Antonia Blumberg for The Huffington Post online; Steven Gray for TIME online; Evgeny Lebedev for GQ online; Carmin Sessin for NBC News online. In 2012, Oxford University Press released R. Andrew Chesnut’s Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint, the first academic depth study of the saint. (My summary of Santa Muerte, below, is taken from these sources.)

"Santa Muerte 20100601 002" by Jim Hobbs. Via Flickr. A "backyard shrine" to Santa Muerte in the photographer's neighbourhood

Santa Muerte is a female personification of death, a Mexican folk saint with her roots in ancient beliefs about and reverence for death. Though denounced by the Catholic Church, Santa Muerte clearly encapsulates identifiable elements of Catholic practice– e.g. as a saintly intercessory figure with shrines as epicentres of worship, identifiable by specific iconography. Santa Muerte has been taken up, in particular, by people to whom the Church has not, or cannot, adequately cater: the poor, criminals, and the LGBT community. The Church has not fought to tackle poverty with enough vigour; cannot answer criminals’ prayers which relate to illegal and immoral behaviours; and has excluded LGBT believers from fellowship and sacraments. What’s more, for people living in communities torn apart by drug and gang violence, Santa Muerte seems to be the ideal choice. As Lebedev remarks: “Because people might die at any moment, they have begun to worship Death, since they believe this might at least give them some protection.”

Whilst there is only one pontiff and a series of authorised ecclesiastical precepts, believers still customise their own religious experiences in various ways. Doctrine, after all, has always been questioned, debated, reformulated. The laity has always managed to express their religiosity in views not necessarily fully palatable to the Church. Santa Muerte is a modern iteration of this phenomenon, but the medieval era is full of religious narratives in which believers try to figure out their religion on their own terms. I’m thinking, here, particularly of the ways in which many medieval holy men and women we study now a “saints” were never actually canonised – but rather, they were taken up as sacred figures by devotees in their locale and beyond. This was the case for the corpus of extraordinarily pious thirteenth-century women I analysed for my PhD: none of the “Holy Women of Liège” ever received the official approbation from the Church in the form of canonisation, but were certainly held up as saints in various ways by their communities. No religion is made up solely of official doctrine: lay believers also play a highly significant role in constructing specific iterations of their own religion, which may just skirt the transgressive bounds of outright heterodoxy. What I’m interested in then, is recognising – and ultimately disentangling – the power dynamics at play in religious worship between the constellation of the Church (officialdom), God (that in which we have faith), and the believer herself. We can best do this work, I think, by casting our eye at both ends of the temporal divide: by recognising that worship forms are in the process of continual renegotiation in a given moment and across time.

Gallery of Images from Visit to Ta'Pinu Shrine, Gozo - September 2011

NB Images are in order of my travel "through" the Shrine: exterior gardens and statuary (including statues of Karmni Grima and Franġisk Portelli); Shrine exterior; ornamentation and religious artefacts inside the Shrine; tokens left for Ta'Pinu by those seeking intercession